2018 Note: As of March 2018, nothing in this analysis has changed. If anything, the issues noted below have only increased in magnitude. Logic dictates that there are still three potential long-run outcomes, which are noted below.

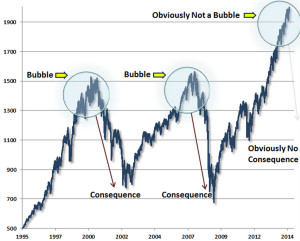

History shows that credit bubbles tend to pop once every 7-9 years, and it appears that the next big bubble pop may be upon us soon. This one, unfortunately, involves not just the stock market, but bonds as well.

Actually, it’s much bigger than that. There are several bubbles all occurring at once: In student loans, in consumer car loans, in stocks, in high-end art and collectibles, in private debt, and in government debt.

In real estate, housing prices still need to come down significantly compared to rents, wages and other prices to be sustainable. This is almost as true now as it was in 2006. College tuition needs to fall dramatically compared to incomes for it to make any sense as an investment. So do car prices and medical costs and stock prices—as well as bond prices relative to their yields.

All these areas have been propped up by extensive currency creation in recent years. There are good reasons that all this freshly “printed” money has not yet showed up in governments’ consumer price indexes. But it is at least clear that each of these areas is priced unsustainably high compared to median incomes, compared to yields, and compared to long-term norms.

Now that the US central bank (the Federal Reserve), has stopped conjuring up unprecedented amounts of new currency, asset prices are just beginning to fall, and quite dramatically. January 2016 saw, literally, the worst beginning to a year in stock market history.

If you think this while scenario through logically, there are really only three potential ways for this to play out in the near term:

One potential end game is that all these inflated prices will fall dramatically. A correction of nearly 50% would be necessary just to get us back to long term norms in the U.S. stock market, for instance.

But another possible outcome—and perhaps a more probable outcome—is that all these asset prices could stabilize at current levels, while the price of everything else rises up around them.

Then there’s a third possibility: A little bit of both. Let’s look at all three:

Scenario 1: The Great Deflation

I think that this is possibly the least likely scenario, so let’s start here. You could reasonably argue that this is what should happen. But chances are that the central banks around the world won’t let it happen.

If asset prices around the world start to drop really significantly, central banks around the world are likely to step in and print up more currency. The stakes for the central banks, and the governments that support them, are probably too high for them not to do this. Letting all these asset prices collapse would mean tidal waves of bankruptcies that would put 2008 to shame.

Although bankruptcies are no fun, they are part of the way markets are supposed to work. Markets are a system of profit and loss, and the “loss” part is just as important as the “profit”. Normally, seeing bad businesses go out of business is a healthy thing. But when it happens systemically and all at once, it can be quite destabilizing in the short term.

In the absence of central bank interference, a major debt deflation probably would have occurred way back in 1999 or 2008 at a smaller and safer scale, but the governments and central banks of the developed world prevented this. If they didn’t have the stomach for it then, chances are they won’t have the stomach for it now, when the stakes are even higher.

In our last two big crashes, inflated asset prices should have dropped dramatically (which they did), many more bad businesses and bad banks should have gone out of business (which they didn’t) and a whole lot of excess credit and money should likely have disappeared from banks’ balance sheets as well (which only happened a little bit.)

But instead, the Federal Reserve started flooding the financial markets with newly-created dollars in the form of Quantitative Easing. They bought the bad loans that no one wanted to buy, and this re-inflated asset prices, effectively kicking the can down the road. Now, we have stumbled upon that can once again.

What will the Federal Reserve do this time? Its new chair, Janet Yellen, has effectively gone on record saying that they will take this same can-kicking approach yet again in response to any large market downturn because—in her words—she believes the Quantitative Easing program “worked so well” the last time. This means that the Fed is likely to fire up the virtual “printing presses” and create as much money as is necessary to avoid a massively deflationary outcome.

If a “Great Deflation” actually did occur, we would have a very severe recession with a tremendous number of personal and business bankruptcies, and a default on a good portion of the US government debt as well.

That would likely result in the most short-term pain, though potentially the most long-term gain—if were were to make necessary reforms. (And that’s a very big “if”.)

It’s also the least outcome to occur in my view, because it is not in the Federal Reserve’s interest; nor is it in the interest of the bankers who own it, or politicians who select its chair.

Scenario 2: The Rollercoaster Crash

I believe this is the second most likely scenario.

I believe this is the second most likely scenario.

There is a reasonable chance that the Federal Reserve would allow asset prices, debt levels, and money supply to fall significantly before rushing in with “helicopters dropping money” on the financial markets once again.

This would mean a tremendous drop in asset prices, but followed by an enormous increase in all prices. If history is any guide, the prices that would rise the most in this case would likely be hard assets, commodities and consumer goods (as well as foreign stock prices) as the market sought a new equilibrium.

Until now, we have been stuffing a good deal of newly-minted dollars into domestic asset prices and bailed-out banks’ balance sheets. But we have also been exporting much of our inflation, in the form of foreigners’ holdings of US dollars, thanks to our status as the world’s reserve currency.

As soon as more money printing occurs, foreign holders of dollars would become less likely to hold onto them, and would instead benefit from exchanging those rapidly-devaluing dollars for hard assets, causing them to effectively bid up prices across the board. This would significantly exacerbate increases in the cost of living for everyday Americans.

Scenario 3: The Great Stagflation

A “Great Stagflation”, similar to the 1970s, strikes me as the most likely scenario for the near-term, though it could occur in concert with some smaller degree of a crash preceding it.

I believe that the Federal Reserve will most likely jump in with additional money printing before markets drop too excessively and a massive deflation begins to set in. They could even do this in response to no crash at all. A large series of new government programs that need to be financed by debt would be enough to trigger it.

This would cause inflated asset prices to stabilize more or less where they are, while hard asset prices and foreign equity prices go through the roof in comparison.

This would result in massive declines in purchasing power for Americans, runaway increases in the cost of living, and we’d see a marked increase in consumer prices, while unemployment rises. But nominally, we’d never see a “crash” in assets.

It would basically be what happened in the 1970s on a somewhat more dramatic scale.

In this scenario, Americans’ 401(k)s and home prices would not fall to dramatically in nominal terms if they dropped at all. They would only in real, inflation-adjusted terms. That is one factor that makes this “solution” much more politically viable.

Americans who have big mortgages or a lot of student loan debt would benefit to some degree. (There are a lot of them. And they vote.) They would effectively be able to pay back their loans with essentially “cheaper” dollars.

Meanwhile, Americans with low debt who diligently save money in dollars would be hammered pretty hard. (There aren’t nearly as many of them these days, unfortunately.) This because each time a new dollar is printed, it detracts relative purchasing power from a dollar that already exists.

Because of that demographic reality, where the US now has a huge proportion of borrowers compared to savers, this will likely be seen as the most politically acceptable outcome. (At least for the near term, which is all politicians really care about.) And so, I believe this is the situation most likely to occur.

Actionable Tips

No matter what, in each of these three scenarios, the same underlying phenomenon occurs:

The real value of US stocks, bonds and bank holdings goes down. Meanwhile, commodities and other hard assets get bid up. And, in either case, the purchasing power of Americans goes down compared to those who live in developing economies throughout the world.

The silver lining is that this will likely lead to less inequality on a global level. But that silver lining is hard to see when it comes at the expense of your retirement savings.

So, if you want one actionable tip, here it is: If your savings are not yet diversified into some reasonable percentage of commodities and foreign stocks and, now is the time to do it. They are both currently dirt cheap in dollar terms.

In the case of massive deflation, their values are very unlikely to drop as much as the value of stocks and bonds, because they have already dropped so far, as deflationary expectations are essentially already “priced in”. In the somewhat more likely case of significant inflation however, those prices will once again go through the roof.

Even if their value didn’t increase in real terms, their relative value would increase compared to other assets, helping you to retain your purchasing power and storing value until more reasonably priced equity and bond investments are available in the future.

Whatever happens, there is no likely case in which the prices of commodities and hard assets would not rise relative to most other paper assets in the coming years.

Especially cheap right now are oil, silver, platinum, palladium, steel, copper, and many soft agricultural commodities.

Gold prices are already starting to ratchet up dramatically, and while they are not the cheapest buy, they are likely to rise first, most quickly and most dramatically do to the metal’s history as a hedge against paper currencies.

There are also great deals in foreign equity markets, when compared to the US stock market. Some of these deals may get better still as the Federal Reserve continues to “play chicken” with interest rates and suggest that it may continue its current tightening cycle.

(Incidentally, many investors still do not recognize that the current tightening cycle actually began way back in 2013 with the “tapering” of QE programs, so we’re actually quite very far into it.)

But as soon as the Fed flinches, which it most likely will, these prices will likely skyrocket. Historically, stocks tend to rise slowly and fall rapidly, while commodities tend to do the exact opposite.

If the Fed actually does continue tightening, these already-depressed values are likely to go down less compared to others, as they have already fallen very significantly on deflationary expectations.

So be forewarned. That’s what’s coming in the relatively near term. Those your likely scenarios. If anyone wants to discuss what happens in the longer term, that’s quite interesting as well.

________________________________________

2018 Update: Not much has changed since this was written, except for one thing: As U.S. asset prices become even more wildly irrational, some people have become even more excited to buy them.

This should not be surprising. It happens again and again throughout history. Market crashes tend to begin on optimism, when the last once-skeptical buyer has gone all-in, and there are no more new irrational buyers left to keep prices unsustainably high.

Those who are blindly buying US stocks today—at even higher valuations when this was written—are doing so under the rationale that tax breaks or deregulation or new government spending may justify such high prices sometime in the future. But this is foolish.

Without their realizing it, people who make this wager this are effectively betting on outcome #3. They are wagering their life savings on a “silent crash”. They are betting on losing their capital to inflation, rather than to a crash.

While this might be wise if nominal returns were all that mattered, in the real world, it is inflation-adjusted purchasing power that matters, not nominal returns. Purchasing power is the true measure of your investments’ performance. And you can’t measure it in dollars over any reasonably long period, because the total quantity of dollars keeps growing.

If the current, excessively-high US stock valuations do end up being justified by future growth in earnings, all that will mean is that inflation will have accrued to such a degree that the purchasing power of your stocks holdings will have decreased. Don’t make the mistake of confusing nominal gains for real ones.

Justin Colletti in an educator, and engineer, and an econ nerd.

PS: Obviously, you should talk to your financial advisor before making any major changes to your portfolio.

I can’t give specific financial advice, but I can tell you what I have done and am doing. And that’s to diversify a reasonable portion of my savings into more modestly-priced foreign equity markets, commodities and physical assets.

Your needs may be different, and remember that there is no one-size-fits-all advice. Investing—even wisely—always carries some risk.